-

Making the Brazilian ATR-72 Spin

by

No Comments

Note: This story was corrected on August 10th at 10:23 am, thanks to the help of a sharp-eyed reader.

Making an ATR-72 Spin

I wasn’t in Brazil on Friday afternoon, but I saw the post on Twitter or X (or whatever you call it) showing a Brazil ATR-72, Voepass Airlines flight 2283, rotating in a spin as it plunged to the ground near Sao Paulo from its 17,000-foot cruising altitude. All 61 people aboard perished in the ensuing crash and fire. A timeline from FlightRadar 24 indicates that the fall only lasted about a minute, so the aircraft was clearly out of control. Industry research shows Loss of Control in Flight (LOCI) continues to be responsible for more fatalities worldwide than any other kind of aircraft accident.

The big question is why the crew lost control of this airplane. The ADS-B data from FlightRadar 24 does offer a couple of possible clues. The ATR’s speed declined during the descent rather than increased, which means the aircraft’s wing was probably stalled. The ATR’s airfoil had exceeded its critical angle of attack and lacked sufficient lift to remain airborne. Add to this the rotation observed, and the only answer is a spin.

Can a Large Airplane Spin?

The simple answer is yes. If you induce rotation to almost any aircraft while the wing is stalled, it can spin, even an aircraft as large as the ATR-72. By the way, the largest of the ATR models, the 600, weighs nearly 51,000 pounds.

Of course, investigators will ask why the ATR’s wing was stalled. It could have been related to a failed engine or ice on the wings or tailplane. (more…)

-

How the FAA Let Remote Tower Technology Slip Right Through Its Fingers

by

No Comments

In June 2023, the FAA published a 167-page document outlining the agency’s desire to replace dozens of 40-year-old airport control towers with new environmentally friendly brick-and-mortar structures. These towers are, of course, where hundreds of air traffic controllers ply their trade … ensuring the aircraft within their local airspace are safely separated from each other during landing and takeoff.

The FAA’s report was part of President Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act enacted on November 15, 2021. That bill set aside a whopping $25 billion spread across five years to cover the cost of replacing those aging towers. The agency said it considered a number of alternatives about how to spend that $5 billion each year, rather than on brick and mortar buildings.

One alternative addressed only briefly before rejecting it was a relatively new concept called a Remote Tower, originally created by Saab in Europe in partnership with the Virginia-based VSATSLab Inc. The European technology giant has been successfully running Remote Towers in place of the traditional buildings in Europe for almost 10 years. One of Saab’s more well-known Remote Tower sites is at London City Airport. London also plans to create a virtual backup ATC facility at London Heathrow, the busiest airport in Europe.

A remote tower and its associated technology replace the traditional 60-70 foot glass domed control tower building you might see at your local airport, but it doesn’t eliminate any human air traffic controllers or their roles in keeping aircraft separated.

Max Trescott photo Inside a Remote Tower Operation

In place of a normal control tower building, the airport erects a small steel tower or even an 8-inch diameter pole perhaps 20-40 feet high, similar to a radio or cell phone tower. Dozens of high-definition cameras are attached to the new Remote Tower’s structure, each aimed at an arrival or departure path, as well as various ramps around the airport.

Using HD cameras, controllers can zoom in on any given point within the camera’s range, say an aircraft on final approach. The only way to accomplish that in a control tower today is if the controller picks up a pair of binoculars. The HD cameras also offer infrared capabilities to allow for better-than-human visuals, especially during bad weather or at night.

The next step in constructing a remote tower is locating the control room where the video feeds will terminate. Instead of the round glass room perched atop a standard control tower, imagine a semi-circular room located at ground level. Inside that room, the walls are lined with 14, 55-inch high-definition video screens hung next to each other with the wider portion of the screen running top to bottom.

After connecting the video feeds, the compression technology manages to consolidate 360 degrees of viewing area into a 220-degree spread across the video screens. That creates essentially the same view of the entire airport that a controller would normally see out the windows of the tower cab without the need to move their head more than 220 degrees. Another Remote Tower benefit is that each aircraft within visual range can be tagged with that aircraft’s tail number, just as it might if the controller were looking at a radar screen. (more…)

-

Recreational Stepping Stones Continue Sporty’s Flight Training Success

by

No Comments

Four years ago Sporty’s President & CEO Michael Wolf took time at year’s end to compile a list of the developing trends in general aviation. I look forward to it each year because Sporty’s probably has more contact with the spectrum of aviators, from enthusiasts and new students to veteran pleasure and professional pilots, than any other entity. And it interacts with them not just as a source of pilot supplies, but also for flight training and avionics and maintenance services.

Half of this year’s 10 trends, writes Wolf, involve the iPad in some way. It’s a MFD for ADS-B In, it sends flight plans to Garmin’s D2 smart watch, it’s replacing paper in commercial and GA cockpits, and it’s changed the contents of a pilot’s flight bag, as well as the aviation apps that run on it. One trend on the list usually deals with Sporty’s Academy, which is dedicated to flight training.

Half of this year’s 10 trends, writes Wolf, involve the iPad in some way. It’s a MFD for ADS-B In, it sends flight plans to Garmin’s D2 smart watch, it’s replacing paper in commercial and GA cockpits, and it’s changed the contents of a pilot’s flight bag, as well as the aviation apps that run on it. One trend on the list usually deals with Sporty’s Academy, which is dedicated to flight training.Pretty much a success from its start in the late 1980s, 2013 was no different, Wolf reports, and the academy, which educates professional as well as pleasure pilots, has concluded its busiest year ever. He attributes part of this success to airline hiring, but most of the school’s continuing success stems from its structure that is built “on a series of stepping stones like the first solo and Recreational certificate, [which] leads to more engaged students and better pilots.” This year, “our dropout rate is approaching zero.”

Since the FAA introduced it in the 1990s, the recreational pilot certificate has been the keystone to success at Sporty’s Academy. While Sporty’s embraced it, and succeeded, with a few exceptions, general aviators and the flight schools panned it. There are many reasons why, but the fundamental reason was that is was different, and people, especially those who exist in a structured activity like aviation, don’t like change. And aviation has suffered because of it.

As we march another year forward in writing the history of powered flight, it is again my hope that aviators and educators will replace their fear and dislike of change with impartial pragmatism. It’s way of thinking where you measure something not on its differences but on its potential to do something better. And if it doesn’t work, stop doing it. And if it does, build on it, adapt it to your situation and circumstances. The effort might, like it has at Sporty’s Academy, support decades of success. — Scott Spangler, Editor

-

Should Aviation’s Past Promote its Future?

by

No Comments

Because it’s usually informative and entertaining, I’m addicted to the bonus material that accompanies DVD movies. When Netflix delivered Disney’s Planes, I devoured the main course and couldn’t wait for the credits to end before digging into the dessert features. One of them was the Top 10 Flyers in aviation history, which were, I’m assuming, selected by the film’s director and producers.

Because it’s usually informative and entertaining, I’m addicted to the bonus material that accompanies DVD movies. When Netflix delivered Disney’s Planes, I devoured the main course and couldn’t wait for the credits to end before digging into the dessert features. One of them was the Top 10 Flyers in aviation history, which were, I’m assuming, selected by the film’s director and producers.Preceding this list, director Klay Hall discussed the movie’s “flight plan” during a visit to Planes of Fame in Chino, California, with his teenage sons. It opened with them standing before a Grumman F9F Panther, a Korean War jet fighter, which his father flew for the Navy. It seemed clear that he was born after the baby boom, and his producer, in a later scene, appeared younger still, so I wondered who would be on their Top 10 list. It was a roster that provided few surprises.

In ascending order, Louis Blériot made the list at No. 10, followed by Bob Hoover, Bessie Coleman, Jimmy Doolittle, Wiley Post, the Tuskegee Airmen, Howard Hughes, Amelia Earhart, Charles Lindbergh, and the brothers Wright. There’s no denying the significance of their contributions, but in drawing attention to aviation, who will they interest beyond already infected airplane nuts? With the exception of Bob Hoover, most of their achievements preceded World War II, which is ancient history to the millennials who are aviation’s future.

It seems to me that many have made important contributions since aviation’s founding figures retired from the sky. And wouldn’t their diverse accomplishments catch the interest of the people now deciding on their futures? Why not compile—and promote—a Top 10 List of those who contributed to aviation in its last 50 years rather than its first half century?

Who would you put on that list?

-

Weigh the Outrage of the FAA BMI Trigger

by

No Comments

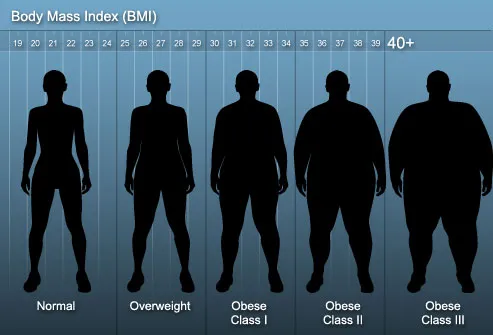

The outrage over the FAA’s recently announced medical certification policy to require pilots with a body mass index (BMI) of 40 or more to be examined for obstructive sleep apnea has been consistent across all channels. (And is it coincidence that the FAA implemented it just before Thanksgiving?)

But not one of the chest-thumping screeds has provided an understandable mental image of what a 40 BMI looks like. “Fat” is the most common adjective, but it does not even come close. Try “morbidly obese,” because a 40 BMI is the threshold for this condition. Such pilots would unlikely be able to squeeze into the cockpit let alone the pilot’s seat.

Let’s put it another way. What is your BMI, your ratio of height to weight? If you don’t know, here’s the link to a calculator. Now, keep adding weight until your BMI reaches 40. How much will you weigh? At 6-foot-5 and 240 pounds, my BMI is 28.5.

The normal BMI range is 18.5 to 24.9. Like many of my age, my BMI is in the “overweight” category, which starts at 25, and it is 1.5 points shy of obesity’s doorstep. And it’s not even close to the FAA’s 40 BMI trigger. To reach that I’d have to push the scale to 340 pounds. A 6-footer would weigh 295 pounds.

When was the last time you you saw a pilot of this size getting in or out of an airplane? So why is everyone giving the impression that the requirement imposes dire consequences on all overweight aviators? Let’s be honest here, many other obesity-related conditions rank higher on the medical certificate denial list.