-

Making the Brazilian ATR-72 Spin

by

No Comments

Note: This story was corrected on August 10th at 10:23 am, thanks to the help of a sharp-eyed reader.

Making an ATR-72 Spin

I wasn’t in Brazil on Friday afternoon, but I saw the post on Twitter or X (or whatever you call it) showing a Brazil ATR-72, Voepass Airlines flight 2283, rotating in a spin as it plunged to the ground near Sao Paulo from its 17,000-foot cruising altitude. All 61 people aboard perished in the ensuing crash and fire. A timeline from FlightRadar 24 indicates that the fall only lasted about a minute, so the aircraft was clearly out of control. Industry research shows Loss of Control in Flight (LOCI) continues to be responsible for more fatalities worldwide than any other kind of aircraft accident.

The big question is why the crew lost control of this airplane. The ADS-B data from FlightRadar 24 does offer a couple of possible clues. The ATR’s speed declined during the descent rather than increased, which means the aircraft’s wing was probably stalled. The ATR’s airfoil had exceeded its critical angle of attack and lacked sufficient lift to remain airborne. Add to this the rotation observed, and the only answer is a spin.

Can a Large Airplane Spin?

The simple answer is yes. If you induce rotation to almost any aircraft while the wing is stalled, it can spin, even an aircraft as large as the ATR-72. By the way, the largest of the ATR models, the 600, weighs nearly 51,000 pounds.

Of course, investigators will ask why the ATR’s wing was stalled. It could have been related to a failed engine or ice on the wings or tailplane. (more…)

-

How the FAA Let Remote Tower Technology Slip Right Through Its Fingers

by

No Comments

In June 2023, the FAA published a 167-page document outlining the agency’s desire to replace dozens of 40-year-old airport control towers with new environmentally friendly brick-and-mortar structures. These towers are, of course, where hundreds of air traffic controllers ply their trade … ensuring the aircraft within their local airspace are safely separated from each other during landing and takeoff.

The FAA’s report was part of President Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act enacted on November 15, 2021. That bill set aside a whopping $25 billion spread across five years to cover the cost of replacing those aging towers. The agency said it considered a number of alternatives about how to spend that $5 billion each year, rather than on brick and mortar buildings.

One alternative addressed only briefly before rejecting it was a relatively new concept called a Remote Tower, originally created by Saab in Europe in partnership with the Virginia-based VSATSLab Inc. The European technology giant has been successfully running Remote Towers in place of the traditional buildings in Europe for almost 10 years. One of Saab’s more well-known Remote Tower sites is at London City Airport. London also plans to create a virtual backup ATC facility at London Heathrow, the busiest airport in Europe.

A remote tower and its associated technology replace the traditional 60-70 foot glass domed control tower building you might see at your local airport, but it doesn’t eliminate any human air traffic controllers or their roles in keeping aircraft separated.

Max Trescott photo Inside a Remote Tower Operation

In place of a normal control tower building, the airport erects a small steel tower or even an 8-inch diameter pole perhaps 20-40 feet high, similar to a radio or cell phone tower. Dozens of high-definition cameras are attached to the new Remote Tower’s structure, each aimed at an arrival or departure path, as well as various ramps around the airport.

Using HD cameras, controllers can zoom in on any given point within the camera’s range, say an aircraft on final approach. The only way to accomplish that in a control tower today is if the controller picks up a pair of binoculars. The HD cameras also offer infrared capabilities to allow for better-than-human visuals, especially during bad weather or at night.

The next step in constructing a remote tower is locating the control room where the video feeds will terminate. Instead of the round glass room perched atop a standard control tower, imagine a semi-circular room located at ground level. Inside that room, the walls are lined with 14, 55-inch high-definition video screens hung next to each other with the wider portion of the screen running top to bottom.

After connecting the video feeds, the compression technology manages to consolidate 360 degrees of viewing area into a 220-degree spread across the video screens. That creates essentially the same view of the entire airport that a controller would normally see out the windows of the tower cab without the need to move their head more than 220 degrees. Another Remote Tower benefit is that each aircraft within visual range can be tagged with that aircraft’s tail number, just as it might if the controller were looking at a radar screen. (more…)

-

Enstrom Artisans Build Helicopters with Personality

by

No Comments

Waggism, playful lightheartedness, is the last thing one would expect to see at a facility dedicated to the deadly serious business of building FAA-certificated aircraft. But then I met Sally, her name printed on an aluminum placard in red Sharpie on the wide end of a fixture used to build tail booms at Enstrom Helicopter in Menominee, Michigan.

Waggism, playful lightheartedness, is the last thing one would expect to see at a facility dedicated to the deadly serious business of building FAA-certificated aircraft. But then I met Sally, her name printed on an aluminum placard in red Sharpie on the wide end of a fixture used to build tail booms at Enstrom Helicopter in Menominee, Michigan.Curious, I asked Dan Nelson about it. Was this the work of some unknown wag, an aeronautical version of Kilroy was Here?. Taking a moment, he carefully put down his Cleco pliers and explained that Sally was the name of the piston-powered helicopter just conceived at the factory. “We started naming them some months ago,” said Dan, a sheet metal master who introduces newcomers to the craft and mentors their mastery of it.

“There was a picture on Facebook of a fleet of our helicopters on the ramp for delivery, and someone said we should start naming them.” The piston-powered F-28F and 280FX get girl names, and boy names identify the turbine-powered 480B. “It’s just for fun,” he said with the unapologetic tone of a father talking about his children.

Perhaps naming these gestational helicopters isn’t so waggish. Expectant parents often name the nugget of their baby to give it an identity, to make it more than a bump, to connect on a more intimate, personal level. The only real difference is that the helicopter’s names stay in the womb. Like all parents, the customers who take the newborn Enstrom home have the naming rights.

The riveted monocoque is just one appendage connected to the welded steel-tube pylon that is the Enstrom’s thorax. Working in robust rotating fixtures that look like complex gyms—yellow for pistons an green for turbines—it takes Enstrom’s state-certified welders about three weeks to weld a pylon, said Dennis Martin, Enstrom’s director of sales and marketing.

The riveted monocoque is just one appendage connected to the welded steel-tube pylon that is the Enstrom’s thorax. Working in robust rotating fixtures that look like complex gyms—yellow for pistons an green for turbines—it takes Enstrom’s state-certified welders about three weeks to weld a pylon, said Dennis Martin, Enstrom’s director of sales and marketing.The welders work with pre-notched tubing, he explained, and the three weeks includes their final fitting, sand blasting, multiple inspections, and a light skim coat of primer that makes imperfections stand out. “We like steel because it’s easier to inspect and repair,” said Martin. “But the main reason is that steel will absorb a great deal of energy.

“If you look at the S-N Curve [a plot of the magnitude of an alternating stress versus the number of cycles to failure for a given material], once it fails, steel continues to absorb energy, which means it is not transferred to the occupants. It doesn’t have a sharp drop off; once aluminum or composites fail, it’s done—it doesn’t absorb any more energy,” said Martin.

“If you look at the S-N Curve [a plot of the magnitude of an alternating stress versus the number of cycles to failure for a given material], once it fails, steel continues to absorb energy, which means it is not transferred to the occupants. It doesn’t have a sharp drop off; once aluminum or composites fail, it’s done—it doesn’t absorb any more energy,” said Martin.Just around the corner, in the composite shop, Tom Retlick is laying up the some seats that combine different layers of foam and glass that work in concert to provide lightweight rigidity, comfort, and a degree of energy absorption. Just celebrating 23 years at Enstrom, he’s surrounded by his work, artistry embodied by the split molds for each model’s cabin and attendant fairings.

The heart of Enstrom’s birthplace is the climate-controlled cube that is the quality department. “It’s such a crazy juxtaposition,” said Roger Hardy after setting a raw casting of the idler pulley for the piston power train in the Conner CNC measuring machine. Just outside those doors there are artisans bucking rivets, welding steel, and laying up and cooking composites “all under one roof with CNC measuring and milling machines.”

“It takes some time to program the machine” to measure dozens of specific points on a part, said Hardy, who starts the effort with the part’s drawing. “But it goes to the exact same point on every part with a consistency that gives a true measure of each part.” He’ll see this part again, after it takes its turn in a CNC mill to become a finished idler pulley.

“It takes some time to program the machine” to measure dozens of specific points on a part, said Hardy, who starts the effort with the part’s drawing. “But it goes to the exact same point on every part with a consistency that gives a true measure of each part.” He’ll see this part again, after it takes its turn in a CNC mill to become a finished idler pulley.After making sure my curiosity had satisfied its current queries, he thanked me, and returned to work, as had all of the artisans I’d talked to this day. Each of them was knowledgeable and friendly, and prompted by my questions, they eagerly shared their knowledge in terms neither patronizing nor overtly technical. As a group, their personality was one of proud parenthood. — Scott Spangler, Editor

-

FAA Bill Creates National Airmail Museum

by

No Comments

Title V of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 is an accumulation of Congressional mandates that don’t qualify for its other titles, like Title IV—Air Service Improvements, and Title III—Safety. This item caught my eye. It’s short, so here’s a copy and paste of the whole thing.

Title V of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 is an accumulation of Congressional mandates that don’t qualify for its other titles, like Title IV—Air Service Improvements, and Title III—Safety. This item caught my eye. It’s short, so here’s a copy and paste of the whole thing.SEC. 526. NATIONAL AIRMAIL MUSEUM.

(a) FINDINGS.—Congress finds that—

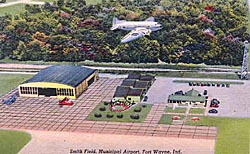

(1) in 1930, commercial airmail carriers began operations at Smith Field in Fort Wayne, Indiana;

(2) the United States lacks a national museum dedicated to airmail; and

(3) the airmail hangar at Smith Field in Fort Wayne, Indiana—

(A) will educate the public on the role of airmail in aviation history; and

(B) honor the role of the hangar in the history of the Nation’s airmail service.

(b) DESIGNATION.—

(1) IN GENERAL.—The airmail museum located at the Smith Field in Fort Wayne, Indiana, is designated as the “”National Airmail Museum”.

(2) EFFECT OF DESIGNATION.—The national museum designated by this section is not a unit of the National Park System and the designation of the National Airmail Museum shall not require or permit Federal funds to be expended for any purpose related to that national memorial.Asking Google about it let me to the National Airmail Museum’s website. Now fundraising, the museum will not only educate visitors about the airmail era, it will describe Fort Wayne’s role in the system’s development. Housed in Hangar 2 at Smith Field Airport, the museum will feature interactive and hands-on exhibits that will give visitors a deeper understanding and appreciation of the trials and tribulations of the pilots and those who supported them. It will also be home to EAA Chapter 2, a gift shop, and a uniquely themed dining experience.

Hangar 2 is itself a bit of history. To quote the website: Built in the 1920s, “Hangar 2 features three large Truscon Steel Company Doors, a highlight unique to Smith Field in the U.S. at the time they were built. The Carousel Hangar, although outside the period of significance defined for Smith Field, is the only example of Clark W. Smith’s patented design ever built. The hangar is characterized by an innovative rotating carousel door. Smith Field’s tie-down area recalls the era before World War II when hangars were used for maintenance rather than storage, and the aircraft had to be tied down to spiral-shaped stakes in the ground.”

Unlike most airports in operation today, Smith Field was not built for or during World War II. It grew then, but Fort Wayne inspected the site in 1919, pilots started learning to fly there in 1923, and it was established at the Baer Municipal Airport in 1925, named for Paul Baer, America’s first ace in World War I. During World War II, when the Army Air Forces appropriated Baer’s name for its airfield south of town, Fort Wayne renamed the airport for its airmail pioneer, Art Smith.

Unlike most airports in operation today, Smith Field was not built for or during World War II. It grew then, but Fort Wayne inspected the site in 1919, pilots started learning to fly there in 1923, and it was established at the Baer Municipal Airport in 1925, named for Paul Baer, America’s first ace in World War I. During World War II, when the Army Air Forces appropriated Baer’s name for its airfield south of town, Fort Wayne renamed the airport for its airmail pioneer, Art Smith. Born on February 27, 1890 in Fort Wayne, he died on February 12, 1926, the second overnight mail service pilot to die on duty. His parents mortgaged their home in 1910 so Art could build his first plane. Teaching himself to fly, he crashed on its first flight. Learning by trial and error, he became a stunt pilot, taking over at the official Panama-Pacific International Exhibition’s stunt flyer when Lincoln Beachey did not survive a crash in San Francisco Bay. During World War I he was an Army test pilot and instructor, stationed at Virginia’s Langley Field McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio. He joined the Post Office after the war and flew overnight mail between New York City and Chicago, and died on his route near Montpelier, Ohio.

Born on February 27, 1890 in Fort Wayne, he died on February 12, 1926, the second overnight mail service pilot to die on duty. His parents mortgaged their home in 1910 so Art could build his first plane. Teaching himself to fly, he crashed on its first flight. Learning by trial and error, he became a stunt pilot, taking over at the official Panama-Pacific International Exhibition’s stunt flyer when Lincoln Beachey did not survive a crash in San Francisco Bay. During World War I he was an Army test pilot and instructor, stationed at Virginia’s Langley Field McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio. He joined the Post Office after the war and flew overnight mail between New York City and Chicago, and died on his route near Montpelier, Ohio.Aviation as we know it today would not exist without the people who created the airmail system and made it work. That they deserve national recognition should be beyond question. Equally important, aviators today should support the National Airmail Museum because in recognizing the dedication and sacrifices of pioneers like Art Smith, we can inspire these traits among those who are building aviation’s future. Scott Spangler, Editor.

-

Lake Michigan Training Saves Combat Vets

by

No Comments

If there is a long forgotten annex that has preserved World War II combat veterans for eventual display at the National Museum of Naval Aviation, it is Lake Michigan. Without the inevitable accidents that occur when new naval aviators are learning to land on an aircraft carrier, we would not now be able to look upon the world’s sole surviving SB2U Vindicator torpedo bomber. We could not caress the dive brakes of an SBD-2 Dauntless dive bomber that witnessed the attach on Pearl Harbor, and fought in the battle of Midway. Nor could we gaze at an F4F-3 Wildcat that started its service in September 1941 with Fighting Squadron 5 aboard the USS Yorktown.

If there is a long forgotten annex that has preserved World War II combat veterans for eventual display at the National Museum of Naval Aviation, it is Lake Michigan. Without the inevitable accidents that occur when new naval aviators are learning to land on an aircraft carrier, we would not now be able to look upon the world’s sole surviving SB2U Vindicator torpedo bomber. We could not caress the dive brakes of an SBD-2 Dauntless dive bomber that witnessed the attach on Pearl Harbor, and fought in the battle of Midway. Nor could we gaze at an F4F-3 Wildcat that started its service in September 1941 with Fighting Squadron 5 aboard the USS Yorktown. They all ended their active service with the Carrier Qualification Training Unit (CQTU) at NAS Glenview, north of Chicago, Illinois. Looking at them today, imbued with the national worship of veterans, some might be critical of the decisions that led to these veterans of the greatest generation spending four of five decades in the depths of Lake Michigan. But the decision-makers of the time were not so constrained. They had a war to fight and win, and that pragmatism overruled all other considerations. And those who appreciate history should thank them for it.

They all ended their active service with the Carrier Qualification Training Unit (CQTU) at NAS Glenview, north of Chicago, Illinois. Looking at them today, imbued with the national worship of veterans, some might be critical of the decisions that led to these veterans of the greatest generation spending four of five decades in the depths of Lake Michigan. But the decision-makers of the time were not so constrained. They had a war to fight and win, and that pragmatism overruled all other considerations. And those who appreciate history should thank them for it.Facing the carrier qualification for thousands of naval aviators and the vulnerability of the ships providing such training in the Pacific, Atlantic, or Gulf of Mexico, training in Lake Michigan seemed the most logical solution. So the Navy put flat tops on two lake steamers and called the result the training carriers Wolverine (IX-64) and Sable (IC-81). Focused on the goal at hand, the Navy certainly expected and planned for training accidents. Probably no one looked to the future and appreciated that, unlike salt water, fresh water does not eat airplanes. It preserves them.

How well is clear on the unrestored patch of painted aluminum on the vertical fin of SBD Dauntless, BuNo 2106. Assigned to the aircraft pool at Ford Island, it survived the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Then it flew with Bombing Squadron 2 (VB-2) from the USS Lexington (CV-2), taking part in raids on Lae and Salamaua, New Guinea. Then it transferred to the US Marine Corps Scout Bombing Squadron 241 (VMSB-241).

How well is clear on the unrestored patch of painted aluminum on the vertical fin of SBD Dauntless, BuNo 2106. Assigned to the aircraft pool at Ford Island, it survived the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Then it flew with Bombing Squadron 2 (VB-2) from the USS Lexington (CV-2), taking part in raids on Lae and Salamaua, New Guinea. Then it transferred to the US Marine Corps Scout Bombing Squadron 241 (VMSB-241). On June 4, 1942, pilot 1st Lt. Daniel Iverson Jr. and radioman-gunner PFC Wallace J. Reid, took off with the other members of VMSB-241 to attack the Japanese carrier Hiryu. BuNo 2106 was one of the few survivors. It returned to Midway with roughly 250 bullet holes in it, a wounded crew, and one working main landing gear. Iverson received the Navy Cross, Reid received the Distinguished Flying Cross, and 2106 got a total overhaul before being assigned to the carrier qualification training unit, freeing up newer aircraft for frontline combat duty.

On June 4, 1942, pilot 1st Lt. Daniel Iverson Jr. and radioman-gunner PFC Wallace J. Reid, took off with the other members of VMSB-241 to attack the Japanese carrier Hiryu. BuNo 2106 was one of the few survivors. It returned to Midway with roughly 250 bullet holes in it, a wounded crew, and one working main landing gear. Iverson received the Navy Cross, Reid received the Distinguished Flying Cross, and 2106 got a total overhaul before being assigned to the carrier qualification training unit, freeing up newer aircraft for frontline combat duty.During a routine carrier qualification flight, on June 11, 1943, a Marine, 2nd Lt. Donald A Douglas Jr., stalled and spun into Lake Michigan, and sank in 170 feet of fresh water. Salvage crews discovered its resting spot in October 1993 and recovered in January 1994 by A&T Recovery for the museum, which restored it. To give visitors an idea of what they started with, the Sunken Treasures exhibit displays an SBD-4 and an F4F-3 Wildcat in pretty much the conditions in which they were found.

The SB2U Vindicator, a two-crew scout bomber, replaced biplanes in the late 1930s and set the stage for its replacement, Douglas’s SBD Dauntless. First flown in 1936, the Navy didn’t order very many, just 58 in 1938 and another 58 in 1940. With a trussed fuselage and largely covered with fabric (construction clearly seen thanks to the open fuselage panels), the airplane was obsolete before the war started, but the Marines fought with them at the Battle of Midway and suffered heavy losses.

The SB2U Vindicator, a two-crew scout bomber, replaced biplanes in the late 1930s and set the stage for its replacement, Douglas’s SBD Dauntless. First flown in 1936, the Navy didn’t order very many, just 58 in 1938 and another 58 in 1940. With a trussed fuselage and largely covered with fabric (construction clearly seen thanks to the open fuselage panels), the airplane was obsolete before the war started, but the Marines fought with them at the Battle of Midway and suffered heavy losses.The museum calls these aircraft Sunken Treasures, as indeed they are. What’s equally compelling are the number of aircraft still in storage at the bottom of Lake Michigan. — Scott Spangler, Editor